This article is based on a talk I gave to the Hook Norton Arts Group in 2009. As you will read, towards the end, Juliet and I have a personal interest in this subject.

Looting has always been regarded as a traditional part of victorious armies and conquerors and also in times of extreme need. This has continued over the centuries but perhaps reached its peak during the Second World War when the Germans actively looted works of art and other valuables from mainly Jewish families.

In 2007 Robert Edsel, an author and historian from Texas wrote a book titled The Monuments Men: Allied Heroes, Nazi Thieves and the Greatest Treasure Hunt in History. Subsequently a film based on the book with thankfully a much shorter title, The Monuments Men was released in 2014.

During WW2 in defiance of the Hague Convention looting was turned into official policy by the Nazis. Works of art whether paintings, porcelain, sculptures, books or manuscripts were acquired by a number of dubious methods. In the occupied countries the acquisition of art treasures was often justified on the grounds that they were created by German artists or were German inspired and therefore returning to their place of origin. It was also argued that these works of art were merely being “protected” and it would be much better if they were displayed in Germany where millions could enjoy them.

In Eastern Europe works of art were simply seized, however, in some instances, receipts were indeed issued. Museum authorities in Warsaw kept an inventory of what had been looted from the city. It amounted to nearly 3,000 paintings of the European School, some 10,000 odd Polish paintings and over 1,300 sculptures. One of the most famous paintings Raphael’s Portrait of a Young Man was never recovered.

Hitler wanted to impose his tastes on the fine arts, in the past he had embarked on careers in architecture and painting. He wanted to change the Austrian city of Linz, where he had spent his youth, into the world’s centre of art. His view of the future was to have a giant gallery devoted to art which would have been a memorial to himself. This project deprived Europe of about 22,000 works of art.

An art expert, Hans Posse, was appointed by Hitler to head Special Operation Linz which was based in Munich. Posse had first choice of the works which were looted either on Goering’s orders or by Alfred Rosenberg’s ERR organisation Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg. The ERR had been established in Paris after the fall of France to sell works of art at low prices, works of art that had been confiscated from Jews. Rosenberg had had a chequered past as he had been the head of the Nazi party in the 1920s when Hitler was in prison. He was a member of the German Labour Party in January 1919, which subsequently became the National Socialist Movement. Hitler only joined the movement in October that year so Rosenberg was a member before Hitler. Rosenberg was captured at the end of the war and sentenced to death following the Nuremberg trials. According to press reports his was the swiftest execution of the ten who were hanged in October 1946.

If there were any items that Posse did not want Goering took them for his own personal collection. What was left was sent to German institutions. In all nearly 22,000 items were sent to Germany which included 10,890 paintings and 2,471 pieces of furniture. However, not content with these organisations von Ribbentrop established his own. This was a “Special Service Battalion” of four companies, three of which operated in Eastern Europe, to strip libraries, museums and scientific institutions.

After the war most of the art treasures were tracked down by the Allied units. These were SHAEF’s Monuments, Fine Arts and Archive teams and the Office of Strategic Services Art Looting Investigation Unit. Much of the loot was found stored in salt mines at Alt Aussee and Grasleben, or in castles in Bavaria and Austria. Gold and artworks were stored in a salt mine at Merkers which was discovered by US troops at the end of the war.

Despite the best attention of the Allies several hundred items including paintings by Frans Hals have never been claimed. Works by Canaletto, Cezanne, Durer, Renoir and Vermeer, to name but a few, have never been recovered. Lake Toplitz in Austria is reputedly the site of where many items were dumped as the Nazis realised that the war was going to be lost. Over the years divers have attempted to recover artefacts with varying success.

Captain James Rorimer of the US Army was one of the “Monuments Men”. He originally enlisted as a private but owing to his background in art, he would later become the director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, he swiftly gained promotion. He was appointed as the head of the Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives Section of the 7th US Army, Western Military District. His chief responsibilities were the discovery and preservation of art treasures hidden by the Nazis, including those of Goering.

I mentioned earlier that the Nazis merely felt that they were “protecting” their spoils. However, with the end of the war and the recovery of several thousand works of art would it prove difficult to return them to their rightful owners? With typical Teutonic efficiency comprehensive records were kept and therefore could be used to return items to those had lost them. Unfortunately many of the original owners had perished in the concentration camps.

In the intervening years many organisations amongst the Allied countries were set up with restitution in mind. However, tracing owners and finding out what happened to works of art has proved to be difficult and all time consuming.

The Hitler Album, which was reported in the UK press in August 2009 contains details of art works stolen by the ERR in 1940. The leather bound book included lists and photographs of 78 paintings by prominent artists whose works sell for hundreds of thousands of pounds. The fate of many of the works, which were stolen from France during the occupation, is still unknown. It is thought that some may have been destroyed during the war and others salvaged by Allied troops and retained as keepsakes.

Until recently there were believed to be only 39 such albums all found by the Monuments Men in Bavaria. These albums were used as evidence at the Nuremberg Trials and later stored in the National Archives in Washington DC. However, two more albums, marked “6” and “8”, were recently uncovered by Robert Edsel. Edsel had been contacted by the nephew of an American G.I. who had discovered the albums in May 1945 at the Berghof, Hitler’s residence in the Bavarian Alps, close to where the other 39 had been found. Unaware of their importance they were taken back to America where they remained in the attic. The initials “R” and “W” which regularly appear next to the inventory numbers in the albums’ index show that many of the paintings were stolen from the Rothschild and Wildensteins, prominent Jewish families at the time of the occupation in France.

The families had been targeted by the ERR because of their valuable art collections. One painting in the album is listed as “R437, Largillière, Bildinis einer dame”. “Portrait of a lady” was the 437th work of art stolen from the Rothschilds, confiscated by the Germans in 1940, the painting was recovered in 1945 by the Monuments Men. It is thought the painting was returned to the family in 1945, and records show it was sold at auction in 1978.

Restitution of artworks did not really become more prominent until the 1980s and early 1990s. For obvious psychological reasons very few claims were made during the 1950s and 1960s. Those who survived the holocaust didn’t want to spend several years in correspondence with various governments and museums. As a result many claims have come from descendants of the original owners.

The opening of archives 50 years after the end of the war and the access to such material created a vast change in future research and collaboration among historians, curators, legal experts as well as governments. Eventually claims will come to an end as the number of claimants will decline. The ability to mount a properly documented case also decreases according to Daniella Luxembourg writing in The Art Newspaper in December 2008. As an art dealer she is very aware of the problem but she has and will continue to sell works for which the provenance after 1932 is unclear.

“Provenance” refers to all previous owners of a work of art, tracing it from its present location and owner back to the hand of the artist. Provenance has many uses, it can help to determine the authenticity of a work, establish the historical importance of a work by suggesting other artists who might have seen and been influenced by it and determine the legitimacy of current ownership.

Many works have been bought and sold in the post Nazi era in good faith. Luxembourg feels that a good solution to deal with future restitution claims surrounding the most expensive works would be to return them to the heirs so that they can be sold and to involve national museums and governments in a process of arbitration which may result in works remaining in public view.

One of the celebrated cases of restitution is that of the Gustav Klimpt paintings which belonged to the Bloch-Bauer family. Perhaps the most well known painting of the collection is Adele Bloch-Bauer I painted in 1907. An Austrian arbitration court ruled in 2006 that this painting and four others had been wrongfully appropriated from Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer during the Nazi era. The court found that all 5 should be restored without charge to his heirs. The 5 paintings were transported to Los Angeles and were displayed for two months later that year. In June 2006 “Adele” was sold for a reported $135m to Ronald Lauder, making it one of the most expensive paintings ever sold. It now hangs in a gallery in New York. The 2015 film “Woman in Gold” commemorates the repossession of the painting.

It would seem that each piece of recovered art has its own story to tell. A Pissarro entitled “Le Quai Malaquais” was due to be auctioned by Christies in June 2008. However, it was withdrawn from sale at the last minute due to infighting between the descendants of its original Jewish owners. The report in the press mentioned “black sheep” and children born out of wedlock.

In the aftermath of WW2 the “Monuments Men” concentrated on the large collections that had been deposited in salt mines and castles as a precaution against air raids. By May 1948 nearly 2.5m objects had been restituted by US authorities in Germany. However, during the war there had been a market for individual objects some of which were bought through the Dorotheum, which was the Austrian state auction house. The auction house was used to sell works of art that were not being reserved for Hitler.

Matters of restitution in Austria were dealt with differently. In 1969 over 8,000 items in state care had still not been restituted. The deadline for claims was extended to 31 December 1970. Due to poor public relations only 71 items were returned. It is believed that information about claims was only made in one Vienna newspaper. The government had claimed that there was insufficient documentation to return the property to its owners. It transpired that there was a mountain of documents but no one could be bothered to check.

Any article about looted art needs to mention the Mauerbach Auction which took place in Vienna over 2 days in 1996. The collection was named after the monastery near Vienna where a vast collection of art works and other treasures had been kept by the Germans. In the early 1950s the Austrian government took possession of the property and undertook to find the rightful owners. This did not happen. During the 1980s an investigative report on the collection was published in an American magazine, ArtNews. After a lot of public pressure the Austrian government decided, in 1995, to transfer the entire collection to the Jewish community in Vienna. It was agreed that all the items would be sold and the money could be distributed to needy Holocaust survivors and to a number of Jewish charities. The auction raised over $14m.

At the beginning I said that Juliet and I had a personal interest in this subject. Juliet’s father was one of those who had artworks looted. His was born in Pilsen, Bohemia, which is now part of the Czech Republic, but lived in Vienna for a time before emigrating to England in the mid 1930s after his parents had died. In 1938 some of his belongings had been put into storage in Vienna with a view to them being shipped here in due course. However, as we know things in Austria took a turn for the worse and his chattels were looted. He was killed in an air crash in 1963, however, prior to this he had managed to get some items restored to him.

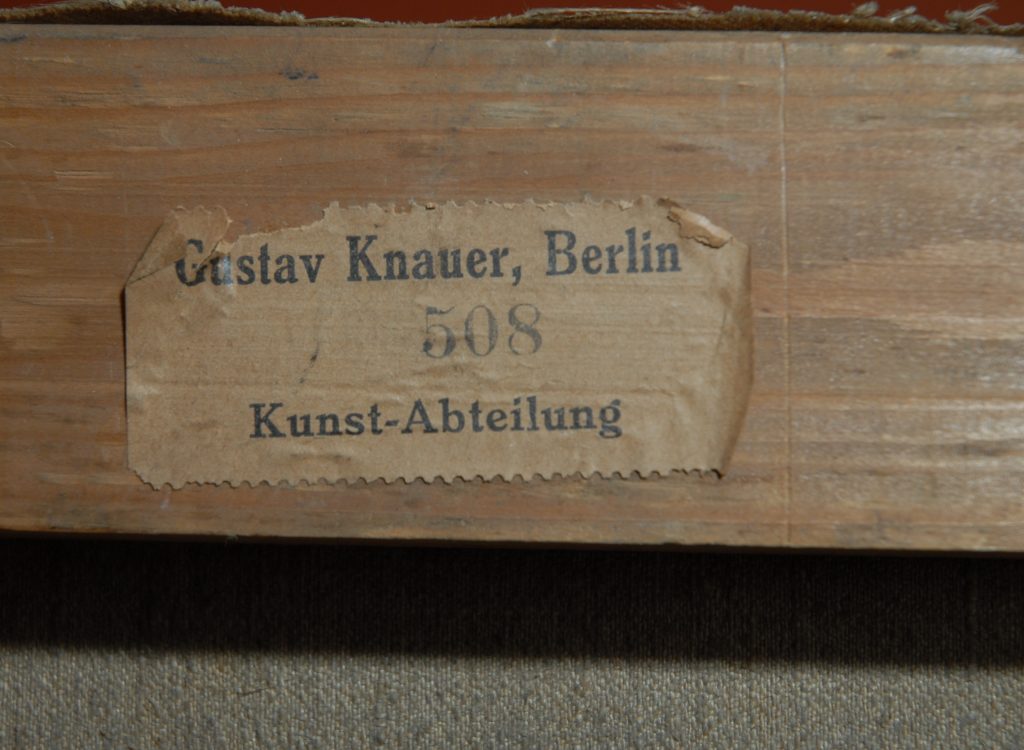

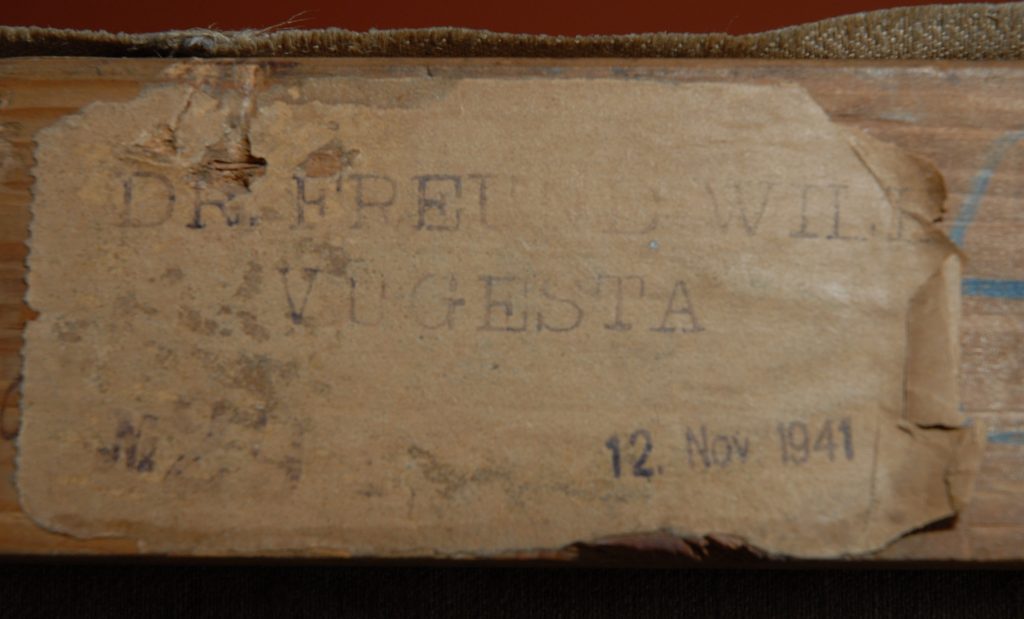

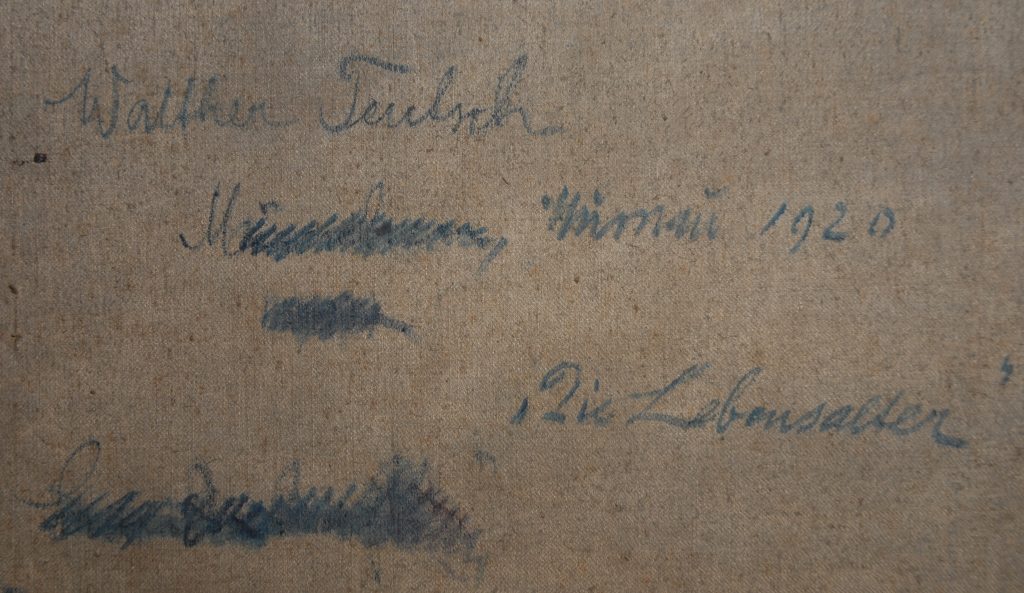

In the subsequent years agents acting on behalf of the family have been able to track down more items. Once such item is a painting by Walther Teutsch entitled Die Lebensalter (The Age) which Juliet and I now have. The photographs accompanying this article show the painting itself and markings on the back. The markings show ownership of the painting plus the fact that it was in the hands of the Vugesta. This was an agency of the Gestapo which was involved with artworks taken from the Jewish community. Another photo shows a label bearing the name Knauer, a storage company that had offices in Berlin and Vienna.

The London based Commission for Looted Art in Europe continues to try to obtain the restitution of stolen art works on behalf of the original owners, well nowadays it will be their descendants. The commission maintains a database, however, there are many works of art listed whose current whereabouts are unknown.

It is good to see that great efforts have been made to reunite stolen works of art to the descendants of the original owners.