© National Records of Scotland

When war was declared in August 1914 thousands of men up and down the country had no hesitation in joining the colours. It was forecast to be short in duration and was envisaged to be all over by Christmas 1914.

The Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith, appointed Lord Kitchener as the Secretary of State for War, the first military man to hold this post. The New Army or Kitchener’s Army as it was popularly known was the result of a massive recruiting campaign to enlist volunteers.

We now know that the war lasted much longer than anticipated. Losses mounted rapidly and conscription was introduced in the shape of the Military Service Bill of 1916. It originally limited conscription to single men between 18 and 41 but in May it was extended to include married men.

Prior to the introduction of the Bill the Derby Scheme had been in existence. This was devised by Edward Stanley, the 17th Earl of Derby. The Scheme stated that men who had attested or voluntarily registered to serve in the military would only be called up when necessary. It was introduced in the autumn of 1915 but was not a success and it was abandoned by the end of that year.

However, due to increased losses as the war progressed the age range was increased in April 1918. Men aged 17 to 51 could now be called up. Throughout this period exemptions from service had been granted but by 1918 further restrictions had been placed on exemption criteria.

From 1916 men seeking exemption from service could apply to local tribunals, appeal tribunals and a central one based in London. Men or employers could claim exemption on the grounds that it was in the national interest to continue their current work. Exemptions were also considered on personal grounds, for example hardship, ill health or conscientious objection. Submitted applications were not all from men unwilling to fight as a large number of applicants had been volunteers. As we shall see exemptions could be permanent, conditional or temporary. All could be revoked.

The vast majority of tribunal material was destroyed at the end of the war. It was felt that this was the right thing to do due to the highly sensitive issues regarding compulsory military service. Two samples of tribunal papers were retained, the appeal records for Middlesex in England and the Lothian and Peebles records in Scotland. It was felt that they should be retained as a benchmark for possible future use. The Scottish records are deposited in the National Records of Scotland (NRH Class HH30) and can be searched online through the Scotland’s People website – www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk. The records for Middlesex are deposited in the National Archives at Kew (Class MH47). Thanks to volunteers from the Friends of the National Archives and the Federation of Family History Societies these records are contained in a searchable database. At the time of writing the records from Kew can be downloaded free of charge while there is a charge of £5 for the Scottish ones. However, the index for the Scottish records is free to view.

My interest in the subject stems from the fact that I produced a booklet about those with a connection to the village of Hook Norton, where I now live, who lost their lives during the Great war. Whilst the Tribunal records do not survive the local newspapers did carry reports of men who sought to either have their call up deferred or to be granted exemption from service whether permanently or temporarily.

Ellen Borsberry applied on behalf of her son, Alfred, whom she employed as a blacksmith. He was her only employee as the other had left. He was also an engineer in the fire brigade, which then, as now, was staffed by volunteers. If he was called up the business would have to close. He was granted an exemption for three months.

The Timms brothers sought exemption on religious grounds. Henry was a teacher in Shipston on Stour and was opposed to war as it was against the teachings of Jesus. He felt that as a teacher he was engaged in work of national importance. Henry said that he would be happy to work in a civilian hospital but not a military one. His application was supported by a letter from the headmaster who told the tribunal that Henry was indispensable as apart from the head himself Henry was the only other teacher in a school of 75 boys. The tribunal ruled that Henry would be granted exemption on the basis that he continued to teach.

Archibald, Henry’s brother, worked 12 acres of land and he felt that the work he was doing was equally of national importance. Letters of support, including one from his father, were submitted. His appeal was granted so long as he continued to be engaged in work of a certified character.

Not all appeals were successful. Fred Busby the village butcher already had a certificate of exemption. However, it was felt that he would be more use in the army than in a village butcher’s shop. His case was adjourned for a short period so that he could produce his books to back up his claims for the number of animals he slaughtered. A further extension was granted in January 1917, but in the end it was terminated. He joined up and was killed on 31 March 1918, aged 40. He has no known grave and his remembered on the Pozieres Memorial in France.

Prior to moving to Hook Norton we lived in Putney, London so it would seem logical to have look for the tribunal records for men from there. Here are two examples.

Claude Mason a tailor of 277 Upper Richmond Road sought exemption on the grounds of hardship on his father who was 76 and a total invalid. Mr Mason senior partially relied on the income from the business which would have to close should Claude be called up. Extensions for exemption were granted on the basis he joined the special constabulary in Putney. Whilst his business was there he lived with his parents in Ealing. In the end his appeal was dismissed and Claude joined the army but survived the war.

Another Putney man Alfred Dawson sought exemption for an entirely different reason. His appeal forms were completed in March 1916 and he sought leave to do so as he was attending an aviation course at Hendon with a view to obtaining a pilot’s licence. He had paid £200 to achieve this and his intention was to join either the RNAS or RFC. Due to a combination of illness and poor weather he did not obtain his certificate until 3 July 1916. A letter to this effect from his instructor is in the file.

The assumption would be that Alfred achieved his ambition to join up as a pilot having paid for his training himself. The file contains a letter dated 12 August 1916 from the Air Department at the Admiralty addressed to the Middlesex Tribunal. It stated that it would not be possible to use his services in the commissioned ranks either as a pilot or observer due to his age. At the age of 29 he was considered too old. On 29 August his solicitors wrote to the Tribunal informing them that Alfred had joined the RNAS as a First Grade Air Mechanic and had received his calling up papers. As a result his solicitors would not be present at the adjournment appeal the following day.

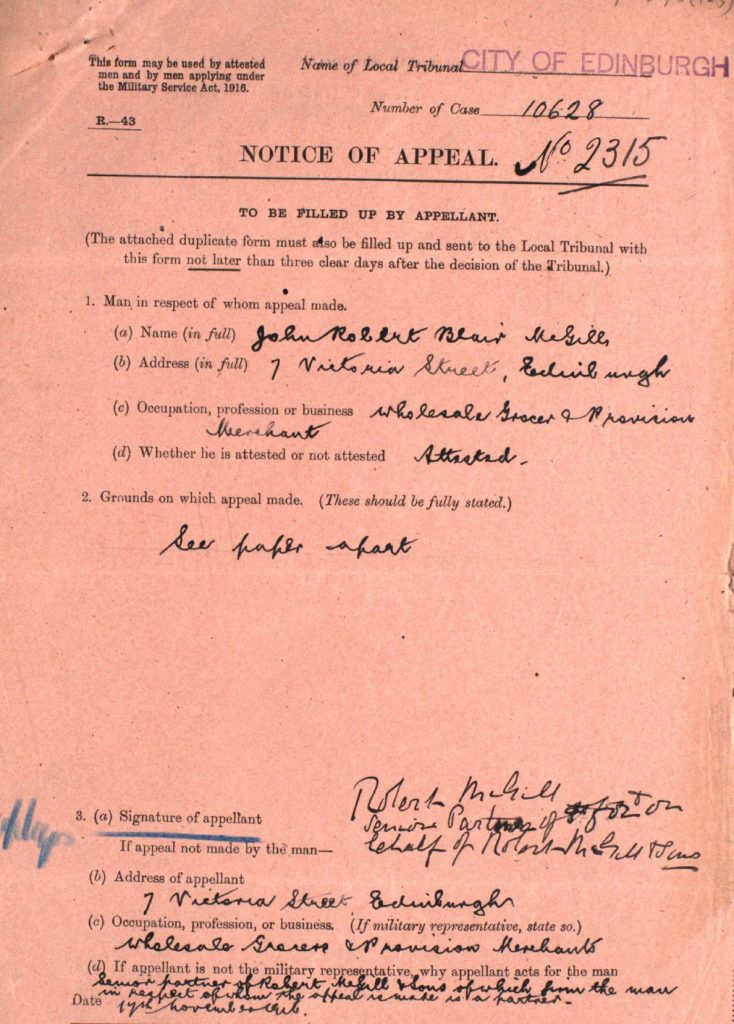

To bring this article closer to home both my grandfathers served in the army during the war. I was surprised to find a Tribunal record for my paternal grandfather, John McGill. My great grandfather, Robert, had a wholesale grocers business in Victoria Street, Edinburgh. Grandpa was a partner in the business along with his father and his brother, Hugh. Hugh, a single man, had already joined the army and was serving in France. John, at this time was 29, married with two young children.

The business employed five others in addition to the partners. Two other employees had joined up. As Robert carried out most of the buying and warehouse supervision an appeal was lodged. The business was a highly successful one with an annual turnover of approx. £20,000. It was claimed that “a good inside man is absolutely essential and one cannot be got”. John’s exemption was extended from May 1916 to December 1916 and he was called up in early 1917. He went on to serve with distinction in the RGA winning a Military Medal during the Italian campaign the following year.

The Tribunals served a purpose and would have been a fair method of granting temporary or permanent exemptions from war service during the Great War.